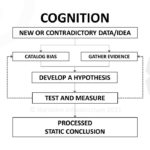

At our biological root

we are subject to eating and breathing, drinking and eliminating. If you would desire to be free of necessity, you would be forced to forgo the need for food and water. You are slave to these necessities more than any indenture imposed by other men: your thirst will slay you in three days, hunger in thirty, air in mere minutes. In the simplest sense, to live is to need, to need is to be enslaved.

We have managed to develop elaborate cultural rituals to spice up our servitude. Often referred to as the “spice of life”, variety is only various flavors of our necessity. It is astounding that we create such extraordinary inter-cultural conflicts around our common needs rather than focusing on ensuring all in our genus are provided for.

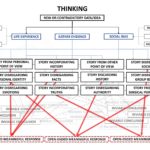

There are no opportunities

only obligations

The drive to compete, to take more than our share, is ancient and the root of evil. We strive to stand taller, to see further, yet we find ourselves atop a lonely ladder, as imprisoned in solitude as much as when we were in cages.

Each new venture becomes territory for our own use that we would deny to others. Any boons we acquire instantly burden us with the threat of their loss. Loss being the normal result of all acquisition, we worry even though out cake is in our hand. Either we will eat our cake, or someone else will eat our cake, or it will spoil. We enslave ourselves to our homes, friends, and pleasures.

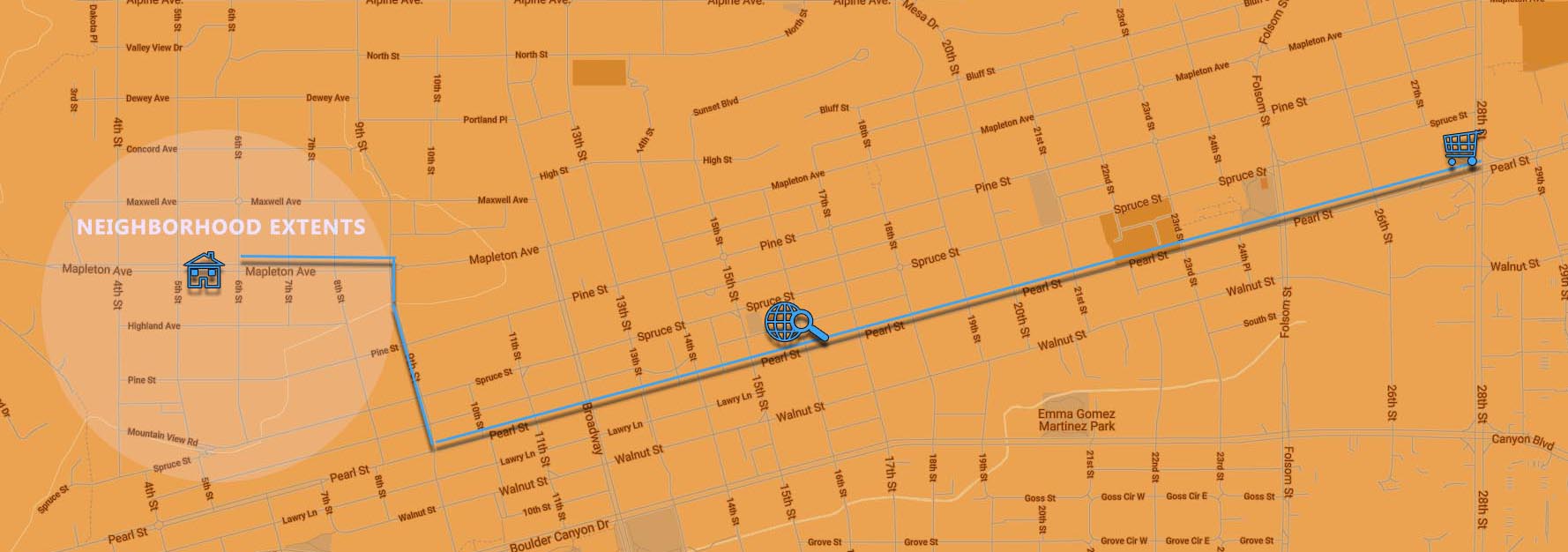

If you want to go fast,

go alone

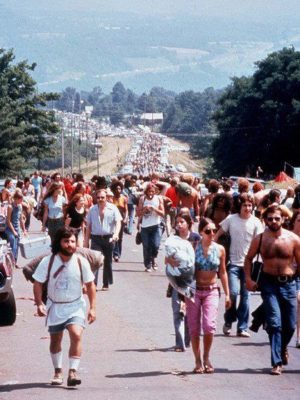

If you want to go far,

go together

-African proverb

Whether in a cage or perched atop your accomplishments, to be alive includes enslavement to necessity. There is a place for the hermit in the wilderness, and those that choose to withdraw have taken their burdens upon themselves and seek little help.

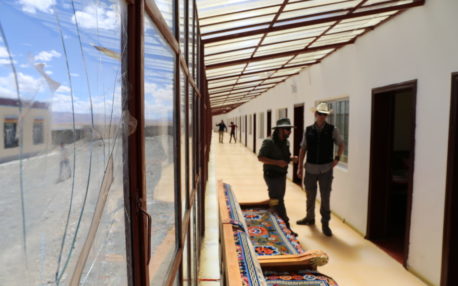

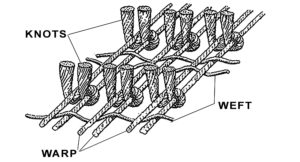

Those of us who choose to remain in the community are tasked with this common world we share. It is an enslavement to our infrastructure that sustains us. In these works is the embodied stories that one person told another that started with “Hey would it not be great if we…” and so we listened to their story. We accepted the obligations associated with that new work be it child-care, potable water, or roads. All these improvements do allow us to live longer, but not forever.