How to Enable Every Ukrainian in Reconstruction and Long-Term Planning

ця стаття доступна українською мовою.

In recovering from disasters such as fires and war, communities often bare the stamp of some singular authority. Such redevelopments are inherently creatures of that author, hence author‑itarian. When singular and total in their narrative, they are total‑itarian.

Building a decentralized archive of local narratives, one immune from manipulation by special interests who would limit the plurality of narratives, is to build an unassailable fortress against totalitarianism. If Ukrainians would build this narrative infrastructure with resources they have access to even now, even if absent from their hometowns, they could rebuild upon return and develop in continuity with their own sense of place

Memories turn “space” into “place”

Our sense of emplacement, via our memories, is triggered by visual references from our space. Evolved urban spaces are reflective of many thousands of authors’/ stakeholders’ stories over decades and centuries held by the landscape. This plural collection of memories embodies the illusive sense of place.

The loss of visual cues from the urban fabric, a loss of the sense of the place, is why the trauma of urban renewal lasts for decades. To mitigate this trauma, renewal should be a pluralistic effort derived primarily from local stories, and ongoing development should leverage the same process by elaborating on existing local stories rather than imposing foreign ideas.

Cross-sectional verses Longitudinal Planning

A significant limitation of conventional planning and urban management practices is the cross-sectional process: only those stakeholders with awareness and time in their schedule have the potential to be involved in discreet projects. Stakeholders who do commit their time and energy are limited to the single project under consideration and those contributions are almost never reused later.

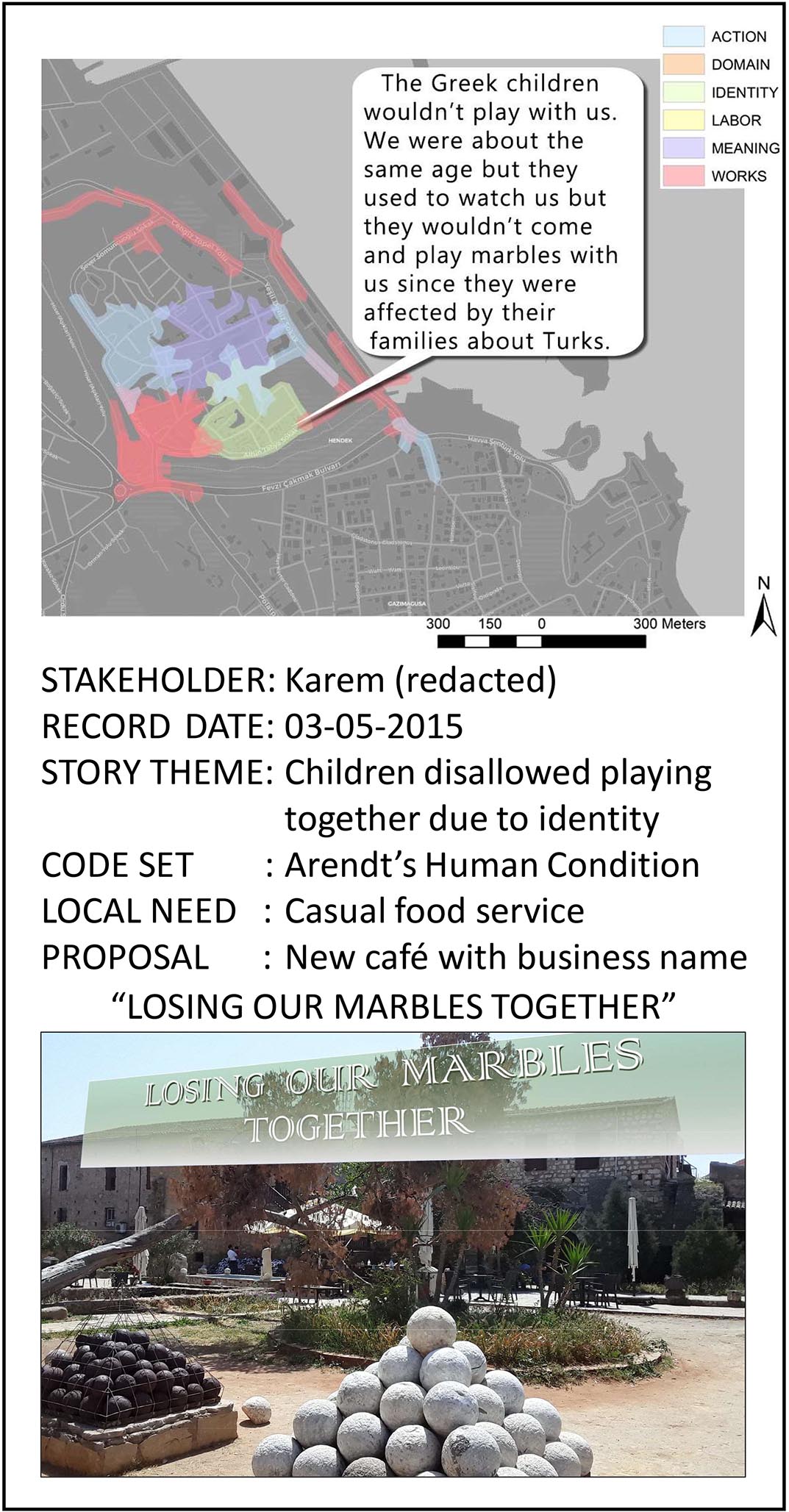

In Narrative Infrastructure, the stakeholders contribute a map of their personal memories (figure 1, upper), discretely mapping their sense of place in a narrative spatial archive. In this manner they are always contributing their geographically relevant story rather than having to respond to each new project. Narrative Infrastructure forever embeds the meaningfulness of their life experiences in the land itself. Every reconstruction or development project can begin generating ideas by narratively extending and building upon the memories of local stakeholders in the spatial archive (figure 1, lower).

When developers fail to use local narratives, opponents can legitimately criticize developers’ ethics for failing to incorporate the known past of the specific location. Stakeholders and critics can make the justifiable claim that the proposal is harming the sense of place (and they will be able to prove this using data from the spatial archive).

This longitudinal and pluralistic approach does not obviate planners, regulators, and developers from doing cross-sectional stakeholder engagement. Details must be addressed with inputs from specialists. But with Narrative Infrastructure, local support is improved because the concept themes are foundationally local, while outreach can be targeted and more efficient.

figure 1. NI in use at Famagusta, Cyprus

figure 1. NI in use at Famagusta, Cyprus

|

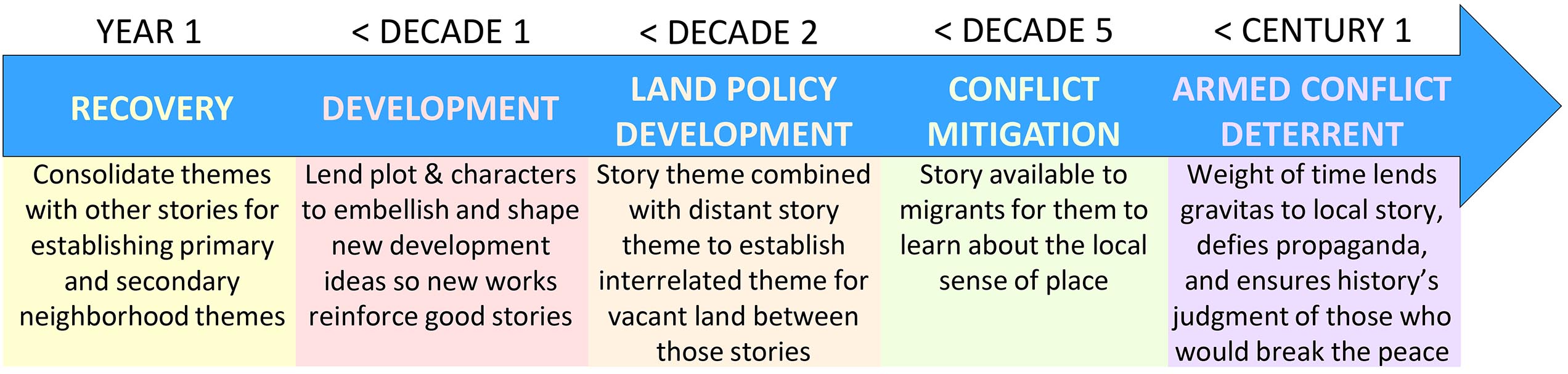

Fig 2. Potential uses of a mapped oral history in longitudinal approach |

Everyone wants to see their lives meaningfully influence their neighborhoods. If the themes of their personal stories are embodied in new urban developments they see, they will feel they have lived meaning-full lives (some examples are included in figure 2). The continuity of their emplaced memories will persist, and they will be more likely to reinvest themselves in those places.

Story collection can begin this week

One or two-hour oral history interviews are the building blocks of Narrative Infrastructure. Using out-of-the-box functionality of Google Earth, a native speaker anywhere in the world can record the voice of a stakeholder and simultaneously map their story. Even when not in their own neighborhood, a stakeholder can review their personal photos and Google Street View to cue their memories.

Deposited on mirrored servers of unrelated universities using an open public ledger (or blockchain), this spatial archive will be tamper-proof. How stories overlap with each other and other spatial data can then be compared graphically.

Narrative Infrastructure exists all around us now, we just need to map it to make it useful.

For 500 generations, urban environments have been developing from one person telling another person a story. Laws are derived from sad stories; development is the result of exuberant stories. Ukrainians are in a unique position to:

01

tell their stories

02

inform reconstruction efforts

03

influence future development of Ukraine

04

and declare their sense of place indestructible

About the author

Jason Murray Winn, AICP, is an architect and urban planner with Alpha Terra Inc. (Texas). He is a recent senior lecturer of urban design at Eastern Mediterranean University, with a pedagogical focus on ethnographic and narratological approaches to stakeholder engagement in the design and planning process. He is the acting director of Narrative Infrastructure, an initiative to establish a community archive of mapped stories for policy, peace-building, and development.

This proposal was in response to the recent APA International Division’s Report on Ukraine’s Post War Reconstruction.

Special thanks to Xenia Adjoubei

Xenia made possible the Ukrainian translation of this article. Learn more about her upcoming classes supported by the Kharkiv School and Ro3kvit Coalition for the reconstruction of Ukraine for an exhibition and education programme involving and supporting Ukrainian refugees.

She is the director at Adjoubei Scott Whitby studio urban design and creative consultancy.