IS THINKING ACTION?

He stood there.

In the middle of a riot, with tensions high and water-cannons on stand-by, he just stood there.

He was not trying to stop a line of tanks.

He was not impeding the British cavalry.

He stood there—in public—

and thought.

In 2013, there was a dramatic uprising in Turkey initially inspired by the desire to preserve a public park. Erdem Gündünz, an artist, was struck by the portrait of the political idealist of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk). There, in the contested space, he stood and thought for eight hours.

The Life of the Mind

This is a modern example of what is described in the “Life of the Mind” (Arendt, 1978) as one of the few moments when thinking had a direct political expression.

Normally, thinking is a withdraw from the apparent world to develop fictional worlds. It is an act of storytelling, of developing “what if?” scenarios.

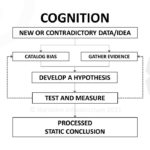

Thinking is not, in fact, a fact-oriented process. Science and cognition is fact-oriented, and seeks to turn the cogs to make the machine of science extrude a new answer that was better than previous answers.

Thinking is not reasonable. There is nothing that needs to lead to thinking, it is not in order of any process, there is no reason to think. When I want to make bread I do not think about it: the reason I add the starter to the pre-mixed dry ingredients is that is the correct order. Thinking about this order would only distract me from the order that has reasons. Thinking withdraws me into my fabricated mental world, and disassociates me from my senses–the sensible world where cooks do their best work.

(caveat: there are moments when both cooks and scientists engage in thinking to create something wholly novel and delicious, but it is not the core of the cookbook or method.)

Thinking is largely an activity without a use. It is somewhat difficult, but we can all think. Most of the time we reason based on past experience from our senses. This “2nd Order” thinking as Schank (1990) and other refer to it is not storytelling, but a mental state that relies on understood patterns that easily lead us astray because they are based on old data, rather than new givens from our environment.

As a useless activity, it, like storytelling, is given little credence. You can’t think a phone into existence. You can’t think a new research paper, you must write a research paper. You can’t think dinner on the table, you must cook. I can’t feed you by telling your a story, but we need stories more than bread itself.

In addition to the setting, and the characters, and the plot of a story, it must spontaneously give rise to a theme. The theme is the take-away, the lesson learned, the warning. The theme is the ultimate culmination of all the action. It is the what everything “means”.

THINKING AND STORYTELLING ARE FOR THE SAKE OF MEANING

Different from truths which must invariably be consistent under all circumstances, meanings are infinitely variable depending on the context. The meaningful-ness of bread is quite different to me if I am starving or if I am gluten-intolerant. Bread is not “true”: to some it is salvation to others it is poison. My individual story makes the bread meaningful. What I think about bread makes it meaningful to me. It is true that bread is a carbohydrate, but “bread is poison” is not true, it means that I am gluten-intolerant.

Keeping with our culinary example, thinking and reasoning quickly gets very triggering: it is true that eating meat ends an animals life, it is not true that “meat is murder”. What eating meat means to some people is equated to the politically egregious act of murder. But the same people would not say when a lion kills a deer that the lion is a murderer. To humans, the ending of a life is murder, but to most other animals it is necessary.

We as humans have polity between us that allows us to live together and cooperate to reduce suffering (both minor and major suffering—from “I want shoes but can’t make them” all the way to “I can’t get any bread, but others will share”). The story we hold in common defines the themes which we all agree to.

When we do not agree on themes is when we have political disagreements. When we do not agree on a theme it is typically because we do not share the same story in all its parts: settings, characters, and plots. In the story of vegetarianism, for example, the meat-eater does not see the animal as a victim in the story. As a result, the theme of the story is quite different between the vegetarian and the meat-eater. Everyone can agree to the facts, but if they do not agree on the characterization, then the lessons learned from those facts are quite different.

STORYTELLING AS ACTION

Thus political differences are all about storytelling. Using stories well was the core of Rhetoric as described by Aristotle. Once a story takes hold it becomes meaningful and inspires actions. This is the goal of all political speech.

When someone stops, thinks, and fails to take action, they are making their immobility meaningful. In that moment, when he refused to be influenced by the themes of either side’s political story, his thinking shocked both sides of a political debate. The thinker, in failing to act, has disavowed the ideas currently prevalent.

That failure to act, is a powerful moment in any political debate because it is the very definition of being “undecided”. His very inaction causes a frisson of potential: something new could arise because a story, a “counter-narrative” is playing out in his mind. Doing so publicly is an inadvertent statement to both the mobility (“mob”) and the ruling party. The subtext is “This is not true. So what does it mean?” This is not civil disobedience, it is thinking.

What followed was examples of political statement using the same inaction. But the original moment was thinking acting politically. The situation caused a dancer to be still.

STORYTELLING IS POLITICAL SPEECH

None of this post should be construed as a political statement in favor of any agenda here above described. It is a discussion on how thinking through the story of relevant actors, in a particular setting, can lead to revealing the meaning behind contention. Doing so publicly is meaningful to all parties concerned. Thinking is available to all of us at all times, and is necessary to examine the narrative of others. In that examination, we can see past our own 2nd order thinking and develop compassion.

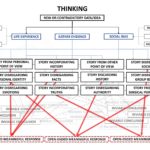

STORYTELLING AS POLITICAL MAP

Narrative Infrastructure proposes that we can speak our oral history and then map those stories. How those stories over-lap spatially becomes a starting point for finding intersections of themes. From this we can build a common world reconciled to our varied stories.

Lean more at NarrativeInfrastructure.org

REFRENCES:

Arendt, H. (1978). The Life of the Mind. New York: Harcourt.

Aristotle. (1929). The Art of Rhetoric (J.H. Freese, Trans.). In Cambridge: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Schank, R. C. (1990). Tell me a story : narrative and intelligence. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Image Credit:

Video Credits:

“Arabian Nights” (2000) Hallmark Entertainment

“The Standing Man – Erdem Gündünz” (2014) SAMAR Media